Holy Week: A Historical and Liturgical Journey

A look at the historical development and liturgical practices of Holy Week.

“The Son of God became a man to enable men to become sons of God.”

— C.S. Lewis, *Mere Christianity

The week leading up to Easter represents the most significant period in the Christian liturgical calendar, commemorating the final days of Jesus Christ’s life, his crucifixion, and his resurrection. Holy Week’s observances have evolved over nearly two millennia, shaped by theological developments, cultural influences, and historical circumstances. Here we explore each day of Holy Week, from its earliest historical references to contemporary liturgical practices across Christian traditions.

The Historical Development of Holy Week

Holy Week observances trace back to the earliest centuries of Christianity, evolving from simple commemorations to the elaborate liturgical sequence we recognize today. The Paschal fast of Holy Week is considered the most ancient part of the Great Fast (Lent), already well attested by the second century in conjunction with the rites of Christian initiation through baptism1. Initially spanning just one or two days, this fast lengthened to four and then to a full six days by the third century1.

Dionysius of Alexandria, writing around 260 CE, provides one of the earliest sources for an incipient ritual of Holy Week in his Letter to Basiliades1. By this period, Christians were already observing special fasting practices during the days leading to Easter. The Apostolical Constitutions (v. 18, 19), dating from the latter half of the 3rd century and 4th century, contains the earliest allusion to marking this week with special observances, commanding abstinence from flesh for all days and an absolute fast for Friday and Saturday2.

The fourth century brought tremendous development in Holy Week rituals, catalyzed by Constantine’s conversion, the influx of new converts, and imperial interest in holy places1. The most valuable historical account from this period comes from Egeria (sometimes called Etheria), a Spanish-Roman woman who pilgrimaged to the Holy Land between 381–384 CE345. Her detailed diary provides the earliest complete description of the early church’s liturgical celebration of Holy Week4.

Palm Sunday: The Triumphal Entry

Palm Sunday commemorates Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, marking the beginning of Holy Week267. The biblical accounts (Matthew 21:1–11, Mark 11:1–11, Luke 19:28–44, and John 12:12–19) describe Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey while crowds spread cloaks and palm branches on the road, shouting “Hosanna!” — fulfilling the prophecy from Zechariah 9:989.

The earliest known record of Palm Sunday observance comes from Egeria’s travel diaries104. She described how believers in Jerusalem would gather near the Mount of Olives and then process down the mountain carrying palm or olive branches, singing psalms including Psalm 118, with the refrain “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord”4.

In contemporary practice, Palm Sunday liturgies typically include three forms of observance: a full procession, a solemn entrance, or a simple rite10. The service often transitions from joyful celebration to a solemn reading of the Passion narrative24.

Holy Monday and Tuesday: Days of Teaching

Holy Monday

On the day after his triumphal entry, Jesus returned to Jerusalem from Bethany, cursing the barren fig tree (symbolizing judgment on fruitless faith) and cleansing the Temple69. The Gospel of Matthew 21:18–43 is typically read on this day11.

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, Holy Monday introduces the “Bridegroom” theme, focusing on watchfulness, symbolized by the Bridegroom coming “in the midst of the night”11.

Holy Tuesday

Holy Tuesday continues Christ’s teachings in Jerusalem, highlighting the parables of the Ten Virgins and the Talents69. Orthodox services continue the Bridegroom theme with hymns stressing spiritual preparedness11.

Holy Wednesday (Spy Wednesday): The Betrayal

Spy Wednesday commemorates Judas Iscariot’s betrayal of Jesus for thirty pieces of silver269. In the East, it includes the final Presanctified Liturgy and the Holy Unction service11. In the West, traditions include the Tenebrae service and Chrism Mass.

The Paschal Triduum

Maundy Thursday to Easter Sunday is one unified liturgical celebration. No final blessing on Thursday, no opening or closing on Friday, and no intro rites at the Vigil — each service flows into the next.

“These great ceremonies are most truly understood as a single liturgy spread out over three days”.

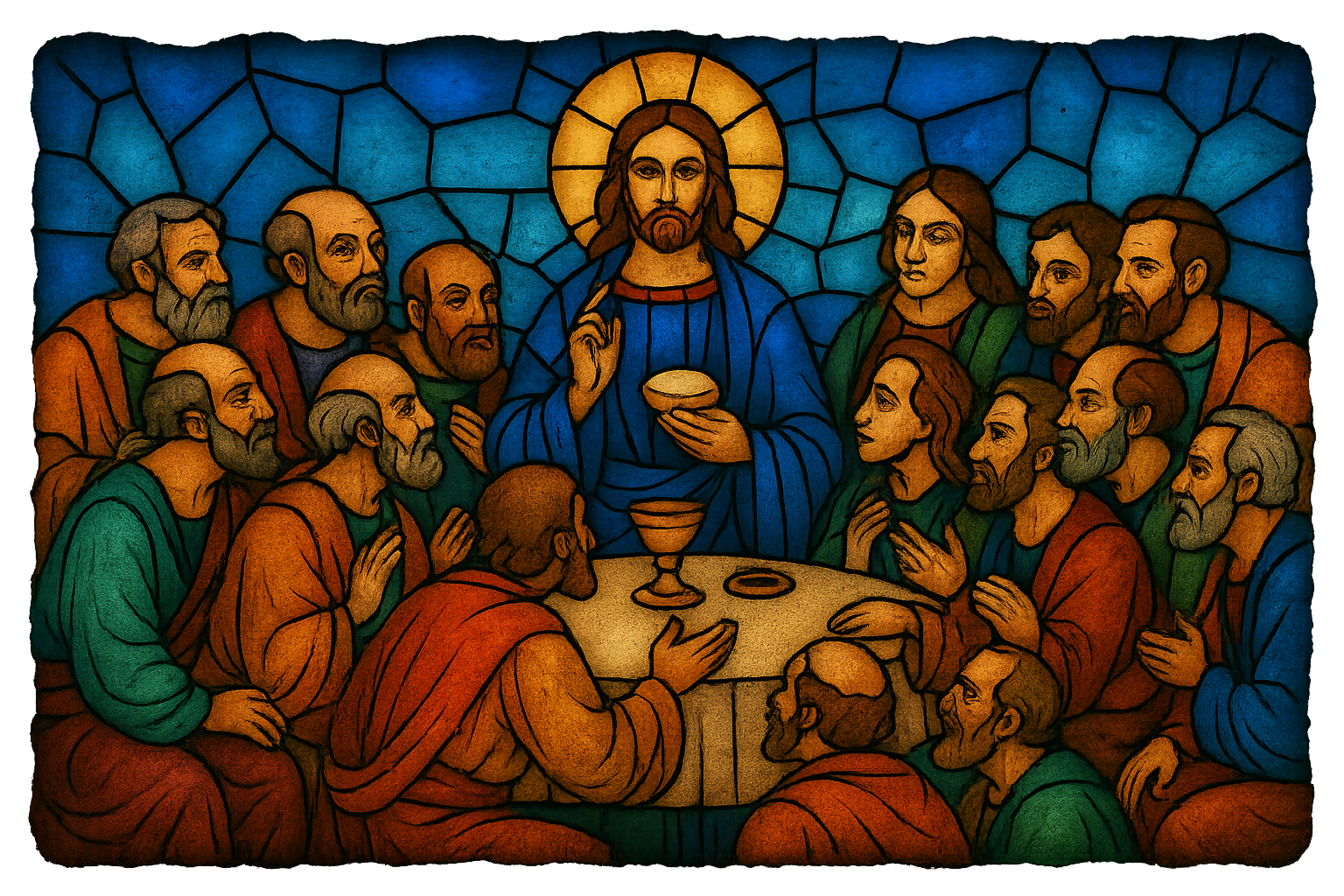

Maundy Thursday: The Last Supper

Maundy Thursday commemorates the Last Supper, the institution of the Eucharist, foot washing, and Jesus’ agony in Gethsemane2116. The term “Maundy” comes from mandatum — “a new commandment I give you” (John 13:34).

Liturgical highlights include:

- The Washing of Feet11

- The Mass of the Lord’s Supper

- The altar stripping

- The transfer and adoration of the Blessed Sacrament

Orthodox services feature the Liturgy of St. Basil and the Twelve Passion Gospels11. Egeria noted the Jerusalem faithful kept vigil at the Mount of Olives without eating afterward4.

Good Friday: The Crucifixion

Good Friday solemnly marks Christ’s crucifixion2116. Egeria describes how the faithful gathered at Golgotha for readings and prayer during the hours Christ hung on the cross34.

Western liturgy typically includes:

- The Liturgy of the Word

- The Veneration of the Cross

- Communion from reserved hosts

- The Stations of the Cross103

In Orthodoxy, the Royal Hours, Vespers of the Taking Down, and the Epitaphios procession are central118. Fasting is observed strictly across traditions21.

Holy Saturday: The Tomb

Holy Saturday remembers Christ’s rest in the tomb269. It culminates in the Easter Vigil — the oldest Christian liturgical observance, as described by Egeria12.

Key components of the Vigil:

- The Service of Light2

- Liturgy of the Word (up to 9 readings)2

- Baptismal rites2

- Eucharist — the first Mass of Easter2

Orthodox tradition includes the Divine Liturgy of St. Basil, transitioning from dark vestments to white118.

Easter Sunday: The Resurrection

Easter Sunday celebrates Christ’s resurrection, the cornerstone of Christian faith2116. Though technically begun at the Vigil, Easter Sunday continues the celebration with joy.

The term “Easter” has pagan roots, though most languages use “Pascha,” linking it to Passover2. Orthodox services begin with a midnight procession and the call: “Christ is Risen!” — answered, “Indeed He is Risen!”118.

Conclusion

Holy Week stands as Christianity’s most profound liturgical period. From Egeria’s fourth-century diary to modern practice, its structure endures. Through Palm branches, Crosses, firelight, silence, water, oil, bread, and wine, the Church leads the faithful to relive Christ’s Passion and Resurrection.

“The purpose of Holy Week is to reenact, relive, and participate in the passion of Jesus Christ.”13

Additional Reading

- Passiontide and Holy Week EWTN

- Holy Week Britannica

- Guide to Lent, Holy Week & Pascha

- 1955 Pacellian Reform

- Egeria’s Diary CCEL